Views: 0

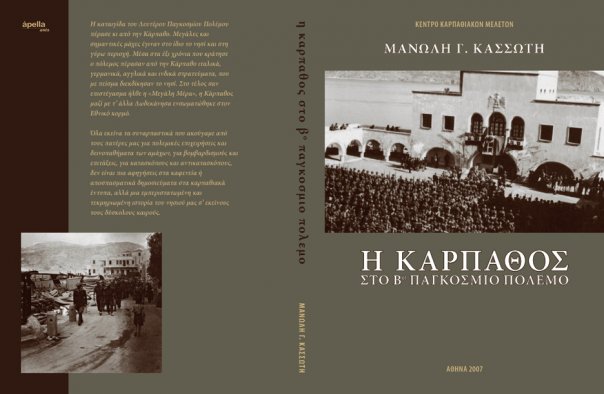

Κarpathos During World War II • Summary of the book contents are captured below

Το βιβλίο του Μανώλη Κασσώτη έρχεται να γεµίσει ένα κενό στη βιβλιογραφία του τόπου µας. Όλα εκείνα τα συναρπαστικά που ακούγαµε από τους πατέρες µας για πολεµικές επιχειρήσεις και δεινοπαθήµατα των αµάχων, για βοµβαρδισµούς και επιτάξεις, για κατασκόπους και αντικατασκόπους, δεν είναι πια αφηγήσεις στα καφενεία ή αποσπασµατικά δηµοσιεύµατα στα καρπαθιακά έντυπα, αλλά µια εµπεριστατωµένη και τεκµηριωµένη ιστορία του νησιού µας σ’ εκείνους τους δύσκολους καιρούς.

Συγγραφέας: Μανώλης Γ. Κασσώτης

146 Beverly Avenue, Floral Park, NY 11001, U.S.A.

e-mail: ecassotis@gmail.com

Επιµέλεια: Άπελλα Νότα

Εκδότης: Κέντρο Καρπαθιακών Μελετών

Ρόδος, ∆ωδεκάνησα

Έτος Έκδοσης: 2007

Author: Emanuel G. Cassotis

146 Beverly Avenue, Floral Park, NY 11001, U.S.A.

e-mail: ecassotis@gmail.com

Design: Apella Nota

Publisher: Kentro Karpathiakon Meleton

Rhodes, Greece

Published: 2007

Copyright: Emanuel G. Cassotis © 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be printed or otherwise reproduced without written permission by the author, except in the case of brief quotations.

ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ

Με ιδιαίτερη χαρά το «Κέντρο Καρπαθιακών Ερευνών» προσφέρει στο αναγνωστικό κοινό την 4η αυτοτελή έκδοσή του, το βιβλίο του Μανώλη Κασσώτη «Η Κάρπαθος στο ∆εύτερο Παγκόσµιο Πόλεµο».

Ο Μανώλης Κασσώτης, εξέχον στέλεχος της ελληνικής οµογένειας στις Ηνωµένες Πολιτείες της Αµερικής, στρέφοντας την πολυετή ερευνητική του προσπάθεια στην ιστορία αφενός της δωδεκανησιακής οµογένειας στην Αµερική κι αφετέρου των γεγονότων του ∆ευτέρου Παγκοσµίου Πολέµου όπως διαδραµατίστηκαν στα νησιά µας, µας χάρισε σειρά εκλεκτών βιβλίων και άρθρων, που πλούτισαν σηµαντικά την καρπαθιακή και τη δωδεκανησιακή γενικότερα βιβλιογραφία. Αξιοποιώντας συστηµατικά τις πηγές κι αγγίζοντας τα θέµατά του µε την αµεροληψία του ιστορικού και παράλληλα µε ανθρωπιά και ευγένεια στις κρίσεις του, κατορθώνει ώστε τα συγγραφικά του πονήµατα να είναι ενδιαφέρουσες ιστορικές µονογραφίες και ταυτόχρονα συναρπαστικά αναγνώσµατα – αφηγήµατα.

Ώριµος καρπός της µακρόχρονης ιστορικής έρευνας του συγγραφέα για την Κάρπαθο στα χρόνια του Πολέµου είναι η παρούσα έκδοση. Όπως λέει ο ίδιος, ήταν από τα παιδιά που οι εικόνες του Πολέµου έµειναν ζωντανές στη µνήµη τους κι αυτό αποτέλεσε την – απαραίτητη όταν δεν πρόκειται για επαγγελµατίες – συναισθηµατική αφετηρία του συγγραφέα, όµως δεν σταµάτησε, όπως κάνουν άλλοι, στις προσωπικές αναµνήσεις και τις αφηγήσεις τρίτων που έζησαν τις καταστάσεις και τα γεγονότα εκείνων των χρόνων, αλλά προχώρησε µε υποµονή και µεθοδικότητα στην έρευνα της πλουσιότατης βιβλιογραφίας, ελληνικής και ξενόγλωσσης. Πάνω στον βασικό ιστορικό ιστό, όπως αυτός συγκροτήθηκε µε τα γραπτά ντοκουµέντα που ανασύρθηκαν από τα επίσηµα αρχεία, ο συγγραφέας αξιολόγησε κι αξιοποίησε πληροφορίες από τις εµπειρίες – δηµοσιευµένες και µη – Καρπαθίων που έζησαν τα χρόνια του πολέµου στο νησί ή πολέµησαν στα διάφορα πολεµικά µέτωπα. Αναζήτησε ακόµα και αποθησαύρισε τις πολύτιµες µαρτυρίες Ιταλών, Γερµανών ή Βρετανών που υπηρέτησαν ή έδρασαν εκείνα τα χρόνια στην Κάρπαθο, η οποία, ως γνωστόν, παρουσίαζε ξεχωριστό ενδιαφέρον για τους εµπολέµους λόγω της προνοµιακής γεω-στρατηγικής θέσης της.

Μαζί µε τα έγγραφα και τις µαρτυρίες συγκεντρώθηκε και δηµοσιεύεται κι ένα συναρπαστικό φωτογραφικό υλικό που συµπληρώνει, τεκµηριώνει και πλουτίζει την έκδοση.

Το βιβλίο του Μανώλη Κασσώτη έρχεται να γεµίσει ένα κενό στη βιβλιογραφία του τόπου µας. Όλα εκείνα τα συναρπαστικά που ακούγαµε από τους πατέρες µας για πολεµικές επιχειρήσεις και δεινοπαθήµατα των αµάχων, για βοµβαρδισµούς και επιτάξεις, για κατασκόπους και αντικατασκόπους, δεν είναι πια αφηγήσεις στα καφενεία ή αποσπασµατικά δηµοσιεύµατα στα καρπαθιακά έντυπα, αλλά µια εµπεριστατωµένη και τεκµηριωµένη ιστορία του νησιού µας σ’ εκείνους τους δύσκολους καιρούς.

Ρόδος, Μάρτιος του 2007

Το ∆ιοικητικό Συµβούλιο του Κέντρου Καρπαθιακών Ερευνών

Κωνσταντίνος Μηνάς, Μανόλης Μακρής, Μάνος Αναστασιάδης,

Μηνάς Μπαλασκάς, Παναγιώτα Βλάχου

SUMMARY

In the annals of human history, there are many examples of nations and peoples who disappeared as ethnic identities from foreign invaders and conquerors. But not for the Greeks; it was enough that a tiny root of their race was left to sprout and flourish new and healthy blossoms in the surprised eyes of their conquerors. The miracle of this great rebirth from the ruins and ashes of the total destruction and calamity was to repeat one more time in its glory in the Greek Dodecanese islands.

The official enslavement of the Dodecanese islands, including Karpathos, began from the time of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem in 1309 and continued with the Turks, who conquered the islands in 1522. But during the Greek revolution in 1821, the Dodecanesians were one of the first to respond to the struggle for independence. The triumphant termination of the revolution found the Dodecanesians able to breathe the sweet smelling aroma of independence, but with the signing of the London protocol of 1830 the islands were returned to Turkey.

In April 1912, during the Italian-Turkish war, the Italians conquered the islands. The Dodecanesians were misled by the Italians with promises and welcomed them as liberators. It did not take much time for the new conquerors to implement their plan to cleanse the Dodecanesians from their Greek heritage. Faced with this harsh reality, they stood like rocks upon which the waves of the Fascist plans would crash. If Mussolini was harsh for the Italians, he was even harsher for the Dodecanesians. The Fascists turned their frenzy against the hearth of Hellenism, the schools and the church, and tried to extinguish the light that warmed and inspired the unsubdued Dodecanesian soul.

The struggles and resistance of the Dodecanesians started to intensify and spread. Their societies of the Diaspora in Greece and in foreign countries, especially in Egypt and America, became the centers of intensified struggle for national survival and restoration. With this background, the Karpathians with the rest of the Dodecanesians all over the world welcomed the coming of World War II; they believed it was their only chance to gain their independence. This book examines and describes the conditions that existed and the events that took place during the war in Karpathos and in the Karpathian communities all over the world.

The War

In the 1930’s Italy started the fortification of the Dodecanese Islands. In the southern part of Karpathos the Italians built a road system and extended the port facilities in Pigadia. Soon after World War II started (September 1, 1939) and especially when Italy entered the conflict (June 10, 1940), the war preparations intensified. The Italians extended the island’s road system to Afiarti where they constructed and fortified a large military airport and installed an undersea communications cable connecting Karpathos with Rhodes and the rest of the Dodecanese. At the same time the Italians requisitioned the private cars, packed animals and boats, recorded the remaining livestock and produced and rationed the food. Many young men of military age escaped to Greece and later (after the Germans occupied Greece) to Turkey to serve in the Greek military forces. Several of them lost their lives trying to cross the open sea with rowing boats.

The Italians fortified the port, including Vronti bay. They placed coastal guns in strategic positions around the port and the bay and installed antiaircraft guns on “Akropolis” and other hills around the port. These positions were reinforced with mine fields, barbed wire, mortars and machine guns. Around the airport the Italians installed several antiaircraft guns and at the promontories close to beaches antitank and machine guns. On the mountain “Profitis Elias” the Italian navy placed a battery with four anti-coastal landing guns. Up north in “Tristomo” bay the Navy built a small home naval base for 4-5 MAS PT boats. On mountains “Orkili” and “Profitis Elias” the Navy installed observatory posts and wireless stations.

The Italian garrison of Karpathos consisted of the Regina and Siena infantry battalions, two machine gun companies, one heavy mortar company, several antiaircraft batteries and one antitank unit. The headquarter company with several supporting units, including a military field hospital, were stationed in Pigadia, the center of military operations. The navy personnel manned the battery on “Profitis Elias,” the naval base and the two observatory posts. Squadrilia 162a, with its pilots and supporting personnel, was stationed at Afiarti airport. In addition, the Police, the Finanza and the civil administration supported the military in its war effort. Colonel Francesco Imbriani was military governor of Karpathos, while the civil administration was under Delegato di Governo Roberto Antico and later under Di Stefani.

As soon as Italy entered the war, the British navy and air force blockaded the Dodecanese and bombed the port, airport and other military installations of Karpathos. The civilian population, along with the military, suffered from the bombings, food scarcity and the dearth of other necessities. When Italy attacked Greece on October 28, 1940, 311 Karpathians, who lived in or had escaped to Greece, served with the Dodecanesian Volunteer Regiment. Later, after the fall of Greece to the invading Germans, many of these volunteers escaped to the Middle East, served with the Greek forces and took part in many battles in North Africa and Italy. Many Karpathians and other Dodecanesians who lived in Egypt, Sudan, Rhodesia, Morocco and other countries in Africa and the Middle East volunteered to serve with the Greek and Allied armed forces.

The Battle of Crete

On May 20-31, 1941, during the “Battle of Crete,” Germany took advantage of Karpathos’s airport, the only airport in the vicinity, which controls the Kassos channel between Crete and Kassos, one of the main entrances to the Aegean sea. The Germans stationed 90 stuka and 50 fighters (Me-109) at Afiarti airport and neutralized the British naval superiority in the area. From Karpathos, the Germans sunk or set out of action 17 British warships and made difficult the Allies’ evacuation from Crete.

After the German intervention in North Africa, they took advantage of Karpathos’s geographic and strategic position. In 1942 the German navy installed a radar on “Agia Kyriaki” hill near Pigadia to monitor the movement of the Allies’ airplanes and warships in the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. Later in 1943, the German radar kept track of the Allies’ airplanes that flew over Turkey from Egypt to bomb the Romanian oilfields. At the same time, in 1942, the German air force installed a listening post at Afiarti airport to monitor the Allies’ communications.

On August 3, 1943, the British sent to Karpathos a two-man intelligence unit to spy on the Italians and provide them with military and strategic information. A month later the spying party left, but on October 20, 1943 there arrived a second mission to spy on the Germans, who in the meantime were in control of the island. The second unit stayed six months and soon after, in April 1944, a third mission arrived. This last mission was forced to leave a couple of weeks later because the Germans became suspicious.

The Germans Are Coming

On September 6, 1943, two days before the Armistice announcement between the Allies and Italy, a German battalion came from Crete and disembarked in Karpathos. After persistent negotiations and some threats from the Germans, the Italians turned over control of the island and captain Bethege, the German battalion commander, became the military governor. The Germans left the Police, Finanza and the Italian civil employees in charge of the civil administration. In addition, 90 out of 4,000 Italian soldiers who agreed to work and cooperate with the Germans were allowed to stay on the island; most of them did not really sympathize with the Germans, but did it out of convenience.

The remaining Italian military personnel were placed in a concentration camp with the promise to repatriate them to Italy. A few hundred at a time were sent to Crete and from there to the Greek mainland. But instead of going to Italy, they ended up in German war factories. During these crossings, 200 prisoners lost their lives to Allied aircraft bombing and submarine torpedoes. Several prisoners escaped from the concentration camp and, with the help of the local people, survived in the mountains and remote places. Eventually, for scarcity of food and other necessities, they gave up and surrendered to the Germans. One soldier, who did not, was captured and executed. Another soldier, with the help of a local family, survived. In the confusion of the Italian surrender many Karpathians got the opportunity and hid rifles, ammunition and other weapons, that later became handy.

During the battle for the Dodecanese, from September 8 to November 17, 1943, several air and sea military engagements took place between the Germans and the Allies in the vicinity of Karpathos. One important air sea battle took place on October 9, 1943 in the channel between Rhodes and Karpathos, with severe losses on both sides. During these engagements several air planes were shot down and several warships and cargo ships were sunk.

At the end of January 1944, the Germans allowed the Greek schools, closed in 1937 by the Italians, to re-open. The Karpathians were pleased with the German decision; the children of the time remember it to this day. The Greek teachers, dismissed by the Italians, were rehired and agreed to work for free. However, it was difficult for the teachers and students to operate because books, school supplies and funds were not available.

From the beginning of 1944 the Allied air force and navy established their superiority in the Mediterranean and many times bombed the port and airport of Karpathos. At the end of January 1944, three British air planes bombed Pigadia. The Germans did not suffer any casualties, but three civilians were killed and three were wounded. A few months later, four British airplanes located four German seaplanes in Pigadia bay. The German planes were bombed before they were able to take off, and all four planes were destroyed. However, the German pilots survived, except one who got disoriented and fell into a minefield.

On April 4, 1944, an Allied commando unit left its base in Turkey for Karpathos, with the mission to destroy the German radar. The patrol got as far as the little island of Alimia. Captured by the Germans, the prisoners were executed. More than four months later, on August 24, a second patrol of the Greek Holy Squadron landed on the west coast of Karpathos; not far from the coast it fell into a minefield and one soldier was killed and three others were wounded. The patrol withdrew, but on its way to its base, the boat, the crew and the patrol were captured by the Germans on the islet of Syrna.

The Germans Are Leaving

After the Allies landed in Normandy (June 6, 1944) and in South France (August 15, 1944) and the Russians advanced from the east and the Allies from the west, the Germans decided, on August 31, 1944, to withdraw from the Dodecanese and the rest of Greece. The evacuation from Karpathos started a few days later; it was first directed to Rhodes and from there, when possible, to the Greek mainland and farther north to Germany. The Germans left Karpathos in four convoys, about ten days apart, each consisting of four to five boats and 200 men. The first two convoys left without any incident, but the third was intercepted by two British destroyers and sunk on September 24. One boat survived and returned to Pigadia with 30 dead and wounded. The fourth and last convoy left the night of October 4, 1944 and, the next morning, arrived in Rhodes (Lindos) without any incident.

With the German departure, the control of Karpathos was left to the Italian Police, Finanza, civil administration and the military personnel who were cooperating with the Germans. The Karpathians, armed with the weapons they hid a year earlier, formed a Revolutionary Committee and revolted against the Italians. After negotiations the Italians agreed to turn over control. The Committee declared Karpathos’ unification with Greece and on October 9 sent to Egypt a small boat with seven patriots to notify the Allies that Karpathos was liberated. The seven patriots almost perished, but after five days of fighting the stormy seas crossed the Mediterranean and notified the Allies and the Greek government in exile.

The British Are Coming

In the morning of October 17, 1944, the British destroyers ‘Terpsichore’ and ‘Cleveland’ arrived in Karpathos from Alexandria with the seven patriots and 27 commandos and in the name of the Allies took over the island. On October 28 arrived the cruiser ‘Black Prince’ with 300 Indian soldiers and on December 16 the cargo ship ‘Korytsa’ with 150 additional soldiers. The same and other transport ships brought weapons, ammunition and other military supplies and foodstuffs for the military and the civilian population. The Indian battalion of the ‘Maharajah of Gwalior’ under major Singh comprised the garrison of the island. The Indian soldiers took position around Pigadia and remained on alert, because the Germans continued to maintain large forces in the nearby islands of Rhodes and Crete. The Germans did not have the means to undertake any major operation against the Allies in Karpathos, but they could send a raiding party, as they did in Tilos at the end of October 1944.

Although major Sigh, later promoted to lieutenant colonel, was the highest ranked officer on the island, Karpathos military and civilian administration remained with the British. Captain Pike was appointed the military commander, captain Charles J. Bonnington was put in charge of civil affairs, inspector MacDonald was put in charge of the Police, Captain George Tabbot was in charge of the port facilities and transportation and captain Wuting was in charge of the justice system. The British took over the importation and distribution of food supplies, sold to the population at reasonable prices to cover the transportation and distribution expenses. The British organized the basic civilian services and left the school affairs to the Karpathians. A few months later, UNRRA set up a branch office under the direction of the Australian Miss Mary Benxon. She took over the welfare system and the undertaking of several development projects providing needed employment for the local people. Later, in the summer of 1946, the British organized the first local election and, after ten years, the Karpathians were free again to elect their local administration.

In addition to their other responsibilities, the Indian soldiers started the clearing of the mine fields left by the departed Italians and Germans. Soon after the liberation of Rhodes, the British brought a team of German soldiers to clear the German mine fields. The remaining Italian mine fields were cleared in 1948, by the Greek army. On June 17, 1945, while military supplies were being unloaded from a boat in Pigadia, the ammunition exploded killing six Indian soldiers and three civilians; tens of others were injured and evacuated to Rhodes for treatment.

For eight months after Karpathos was liberated, Rhodes remained under German control. Many people were dying from food shortages and the Germans allowed them to go to Turkey and from there to Karpathos. From November 1944 to April 1945, 4,000 refugees came to Karpathos and the British built a refugee camp in Afiarti to house them. The refugees were fed and provided with medical care and other necessities and soon after Rhodes was liberated they were sent back to their native island.

Unification

During the war, the Dodecanesians of the Diaspora, and especially those living in the USA, made a significant contribution to the war effort. They cooperated with the OSS, providing military and other intelligence information and several hundred Dodecanesians, including 200 Karpathians, served in the USA military forces. At the same time, they took action to make sure that after the war the Dodecanese would be united with their motherland. On October 24, 1943, the National Dodecanesian Council of America called a Pan-Dodecanesian meeting in New York City, with the participation of Dodecanesian representatives from 12 countries. They issued a proclamation asking the Great Powers to award the Dodecanese Islands to Greece after the war. The Dodecanesians persuaded the press and influential politicians, clergy and academicians to support their cause and try to influence the American government.

The Great Powers, at the Peace Conference in Paris, decided to award the Dodecanese Islands to Greece. On February 10, 1947 the Peace Treaty between Greece and Italy was signed, which turned over the islands to Greece. On March 31, 1947 Great Britain turned the military administration of the Dodecanese over to Greece. Admiral Pericles Ioannidis was appointed the military governor of the islands and lieutenant Panagiotis Psomopoulos took over the military administration of Karpathos. March 7, 1948 was proclaimed the official date of the unification of the Dodecanese with Greece, after King Paul (of Greece) visited Rhodes on the same day. On October 14, 1948 King Paul visited Karpathos along with the other islands. After six centuries the Karpathians together with the rest of the Dodecanesians realized their dream. At last they were free!

Emanuel Cassotis